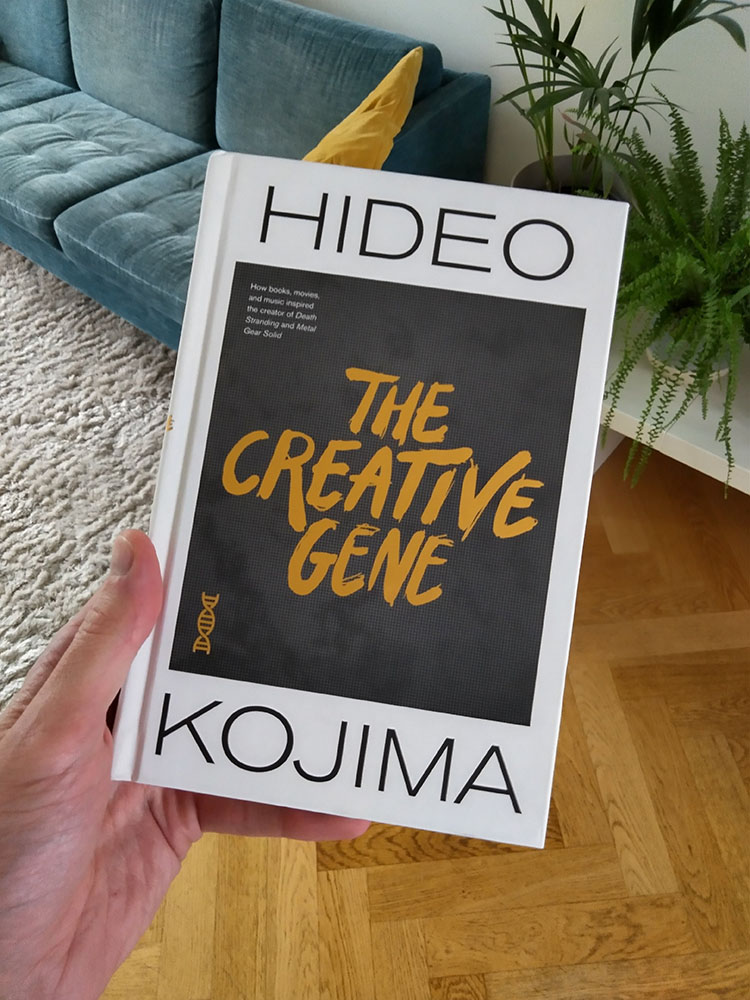

I’ve been inspired by Hideo Kojima for almost as long as I’ve been a game developer. And yet, when I bought his new book, The Creative Gene, it was not with the intention to read it. Not knowing much about it, I anticipated a ghost-written debacle full of mundane trivia. It could at least become a nice coffee table decoration, I thought.

I’ve been inspired by Hideo Kojima for almost as long as I’ve been a game developer. And yet, when I bought his new book, The Creative Gene, it was not with the intention to read it. Not knowing much about it, I anticipated a ghost-written debacle full of mundane trivia. It could at least become a nice coffee table decoration, I thought.

I thought wrong.

The book barely mentions Kojima’s games – there are no tidbits from Metal Gear Solid development, no trivia about Death Stranding, mundane or otherwise. Instead, I was served a collection of essays Kojima wrote for Japanese magazines a decade ago. In each of them, he inspects a book, a movie, or cultural phenomenon that inspired him at some point of his life. Some were a major influence on him. “If I hadn’t encountered this movie,” he writes about Blade Runner, “I would not be who I am today.” Other inspirations were less serious, almost funny. “When signing autograph boards,” he writes in the chapter about anime The Genius Bakabon, “I’ve drawn Bakabon’s dad in the corner on more than a few occasions.” Despite such a wide topic, I noticed an overarching theme.

The essays are not just simple reviews. In all of them, Kojima adds flavor by sharing fragments of his life. For example, a novel Hankyu Densha lets him remember a commuter train from his childhood: “For me, the Hankyu Railway is not just a means of getting from one place to another, but a time machine connecting my memories to my hometown.” I realized that the writings, published between 2007 and 2013 and sorted chronologically, are time machines themselves.

Because enough time has passed since the texts were published, I could spot seeds that later bloomed into actual games. In 2012’s essay about Ágota Kristóf’s The Notebook, Kojima asks “What does it mean to lose one’s native language?” Three years later, he will develop this theme into one of the plots of MGS5: Phantom Pain. Elsewhere in the book he almost matter-of-factly says “I went to Iceland on vacation,” not yet realizing how strong an impact it will have on the environment in his next project, Death Stranding. But only rarely could I identify such clear links; most subjects he writes about influenced him indirectly – the same way Kojima’s work initially influenced me indirectly. I didn’t even need to play his games to be drawn to them.

Back in 2003 I played Hawk in Nets, a mod for Operation Flashpoint. It took a serious military game and turned it into a MGS look-alike, full of tactics, espionage and action. I was instantly mesmerized, and embraced the same style when developing my mods. A couple of years later, lacking PlayStation 2, I couldn’t experience MGS3: Snake Eater first-hand. So I watched and rewatched its English and Japanese trailers, dissecting them scene by scene and recreating my favorite parts. It’s ironic that the first Kojima’s game I ever played was a PC port of MGS2 subtitled Substance, for it’s the substance of his stories that I failed to see. When designing Arma 2: Private Military Company DLC in 2010, I worked tirelessly to capture the melancholic mood of MGS4: Guns of the Patriots reveal trailer, going as far as to imitate its music, titles and color palette. But among all that surface glitter, the reason for the melancholy was lost on me.

MGS4 is a critique of how turning war into a for-profit business can transform society. Kojima’s other games, despite being mainstream entertainment, contain similar thought-provoking themes. ”I incorporated a story and a message into video games – two elements largely considered unnecessary,” Kojima acknowledges about his early projects. Only a handful of authors, let alone game developers, have the ability to sense cultural changes and comment on them before they become relevant. Private military, fake news, or stranded isolation – what inspired him to choose those?

The answer was right in front of me. At first glance I thought Kojima writes about movies and books (and railways) that inspired him. A collection of essays, sprinkled with fragments of his life. But the opposite is true. The Creative Gene is a biography in disguise. In it, Kojima remembers pivotal moments of his life, and uses the essays only as a framing device. “I was never able to talk to anyone about my chronic loneliness,” he reveals about his teenage years, before explaining the effect Taxi Driver had on him. “It wasn’t that the movie taught me to battle my loneliness; it taught me how to keep its company.” Through the lens of the movie, he shares a painful experience that left a mark on his games. It’s no coincidence that all his protagonists are solitary men, unable or unwilling to share their burden with others. But by far the most impactful inspiration was the one which was also the most tragic.

“My father’s early death contributed to a lack of role models in my life,” Kojima writes about a loss that rippled throughout his childhood as well as his career. He often returns to it in other essays, and in his stories. The plot of MGS3: Snake Eater is defined by the protagonist being forcefully separated from his life-long teacher. MGS2 is about questioning the current mentor and accepting a new one. Similarly, Death Stranding’s Sam spends the whole game trying to reconnect with his adoptive and real parents. For Kojima and his heroes alike, these were moments of sorrow, but also growth: “I was convinced that by losing my father in body, I’d lost him.” he writes, before striking a more optimistic note: “But I was wrong. He is still inside me. I carry his voice within me.”

The book reminded me how important it is to keep opening myself to a wide range of inspirations, and, more importantly, to seek their true meaning. But without context of my own experience, my own life, those inspirations would be hollow.

Among others, Kojima references American movies, Japanese anime, European books, or British music. But neither defines him. Not beholden to a single source of inspiration, but carving his own way, he unapologetically concludes, “I’m not Western. I’m not Eastern. I’m not Japanese. I’m Hideo Kojima.”